Body-to-Body: The Works of Donigan Cumming

Graphic Conception

Simon Guibord

Development

Lima Charlie

Project management

Julie Tremble

Production team

Julian Ballanster

Karine Boulanger

Audrey Brouxel

Marion Lévesque-Albert

Denis Vaillancourt

Sami Zenderoudi

Camille Bour

French to English translation

Sarah Knight

English to French translation

Colette Tougas

French revision

Colette Tougas

English revision

Edwin Janzen

ISBN : 978-2-922302-06-6

Tous droits réservés

L'artiste, les auteurs et Vidéographe, 2020

Vidéographe

4550 rue Garnier

Montréal, QC H2J 3S7

514-521-2116

info@videographe.org

videographe.org

vitheque.com

Nous remercions le

Cette publication a été rendue possible grâce au soutien du

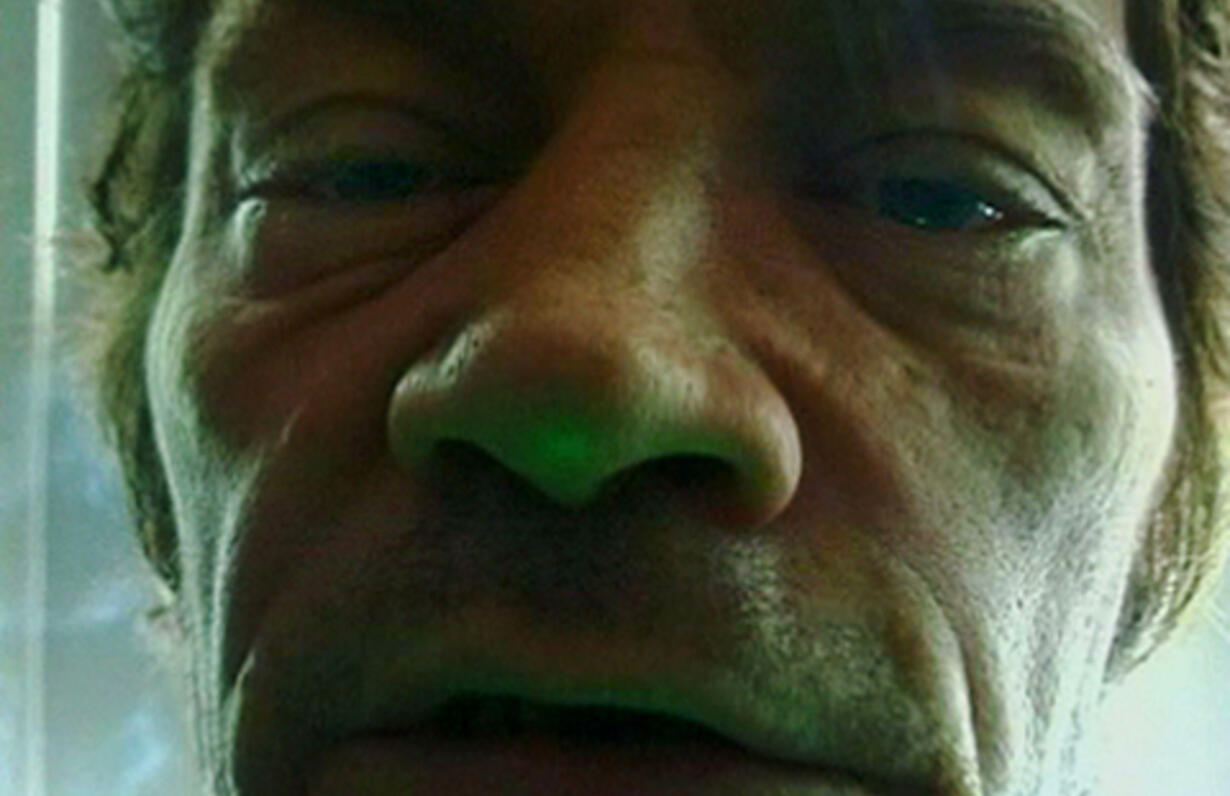

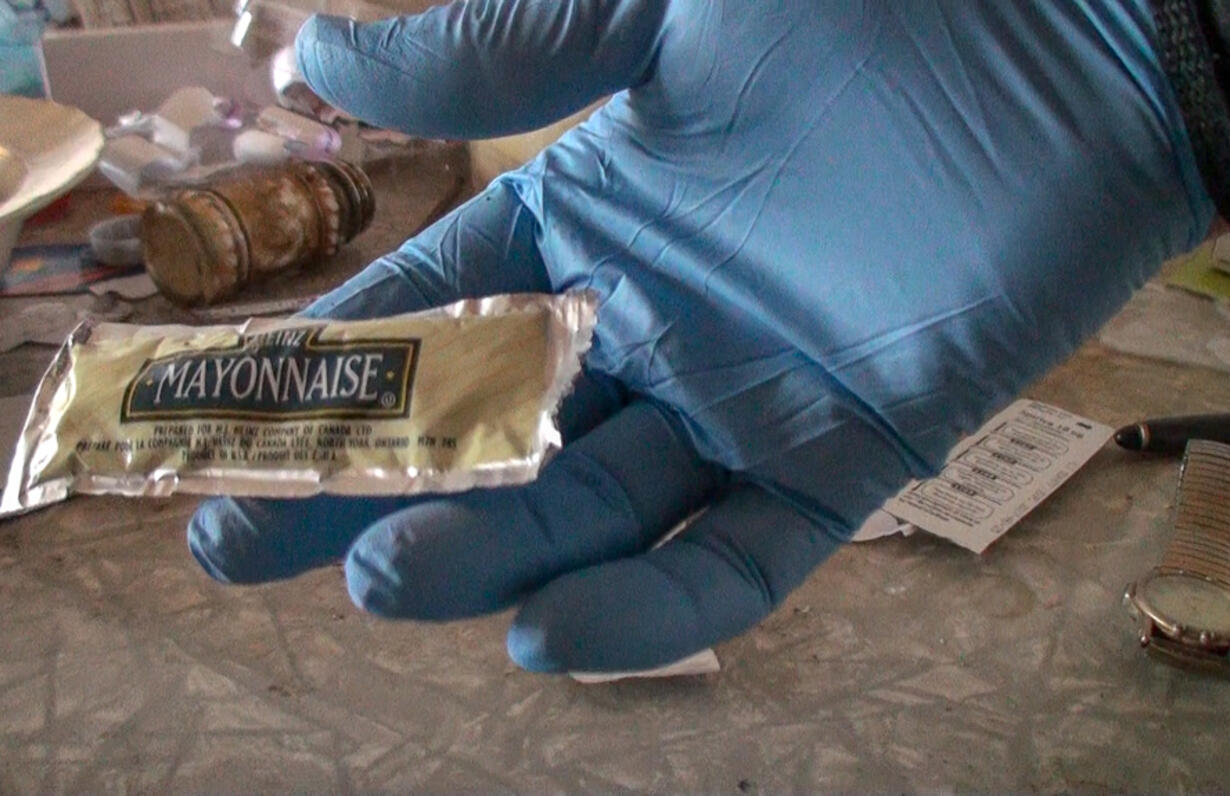

![[ Fig. 01 ] <i>Voice: off</i> (video still), 2003.](/sites/default/files/styles/fixed_width_480/public/advancedpublications/videos/13184/x04voiceoff0.jpg,qitok=frA6hUh-.pagespeed.ic.Gnz1BhnY5d.jpg)

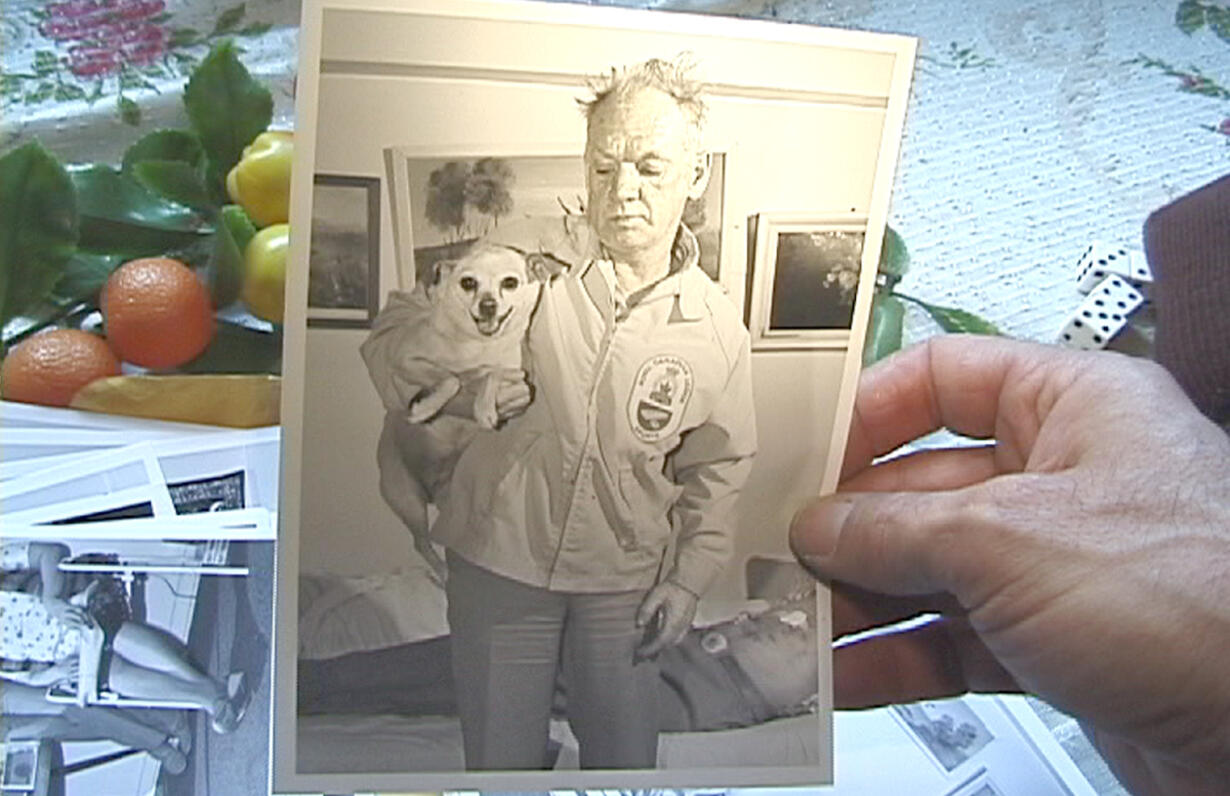

![[ Fig. 01] <i>If only I</i> (video still), 2000.](/sites/default/files/styles/publication_teaser/public/advancedpublications/audios/13136/x50a-18-38anotherone5.jpg,qitok=CRmroRwY.pagespeed.ic.dazwn370jo.jpg)

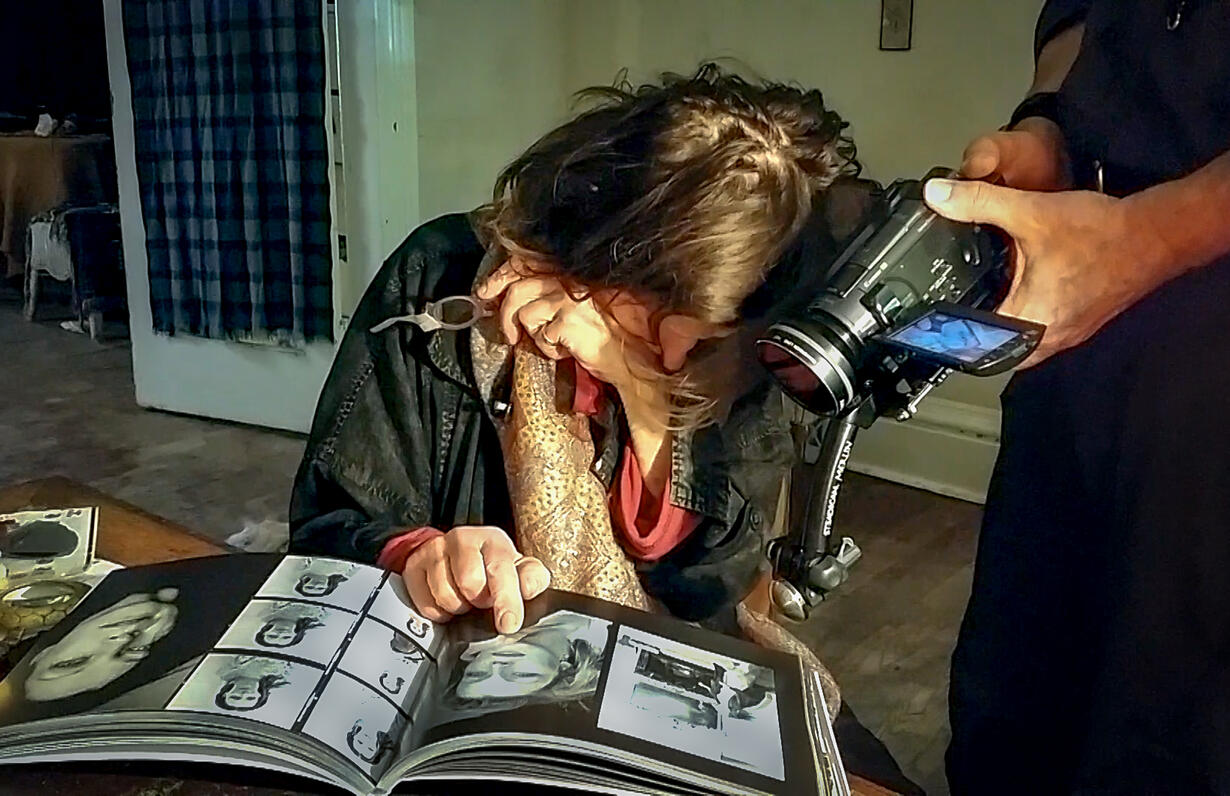

![[ Fig. 01 ] Fountain (video still), 2005.](/sites/default/files/styles/title_teaser/public/advancedpublications/scenarios/13139/x055q43b-24-30exception.jpg,qitok=l3UY8sRd.pagespeed.ic.EoOKBIfaq9.jpg)