marshalore : Nomadic Thoughts

Nomadic Thoughts

The works of marshalore have a singular character: they exert a troubling mirror effect on the observer. They stay with us as soon as we are exposed to them. They resonate. The impression they leave at first contact wends its way through memory and imagination. Think of marshalore’s works, and a few words emerge spontaneously: voice, language, physicality, materiality, sensuality. Then, a second wave breaks: face, space, text, movement, story, silence.

marshalore, a multidisciplinary artist, discovered video in the mid-1970s. She went on to create single-channel videos, performance pieces and installations incorporating video and other media. But one medium remains at the core of her œuvre: “Television was the perfect medium to inundate, engulf, flood, to convince, affirm and assure—a direct line to the open spaces between symbol and conditioning.” 1

A “videographed” body speaks, tells, keeps quiet. This “videographed” body cries out, trembles, exults, emotes. Hands trace words, caress, write. Hands for filming, watching and showing.

sans titre © marshalore

woman/women

A woman sings, accompanied by a man at the piano, bare-chested; it is summer in Montréal. A woman crosses an empty gallery space, lies down on the floor. A woman slips on a glove, coats it in Vaseline and caresses her face, her mouth. A woman slips her hand beneath her clothes, caresses her sex. A teen speaks to the camera and confesses her inner tragedy. A woman whirls around at a busy intersection. A woman puts on makeup, drinks a glass of wine, becomes emotional, cries. A woman covers her face in menstrual blood. A woman walks in an alleyway, melts into the space.

At the heart of the work is a body—that body that marshalore refrains from associating with one person, with one woman, with the artist. A resistance, a reserve that she expresses in the exhibition catalogue Art et féminisme:

"In the hierarchy of “labelling” I really can’t say if I am a person or a woman first. In my art, the exploration of personal, political and social symbols cross and merge into all the aspects of my identity. Ultimately my self, my feminine identity is underlying subjective influence in all my work. And ultimately it is merely another tool for unravelling another clue in the puzzles and parables we confront. It exists neither for praise nor contempt and certainly not to be ignored." 2

This is in 1982. Twenty-one years later the artist reflects further:

"I wouldn’t call myself a physical person and yet, when a creative moment came—more often than not, [I] had my body as a tool for experimentation and curiosity… It was a cultural norm of the milieu I was in to use the body—the sexual revolution, take a lot of drugs, change your diet, become a vegetarian, go back to the earth, go back to the city, dance all night—it was very much a cultural influence." 3

marshalore’s stance is eloquent. It suggests that there is not one body, but rather many bodies: body-tools conducive to experimentation and curiosity. There is she who narrates, who remembers, who invents. The body can be unpredictable, paradoxical. There is she who metamorphoses, cross-dresses, sings, keeps quiet, yells, desires. There is also she who observes, analyzes, criticizes and, through improvisation, crosses private, political, taboo spaces:

"One can improvise in a role when one plays it out given the basic structure and foundation of a set of circumstances. In the video, You must remember this, I put myself in the position of being a young girl, a young woman and an artist, three different roles, and I play them out using the structure of how we’re conditioned. The paradox of conditioning. In this case it was the stylized blues and jazz songs of the 30s and 40s which talk about men beating women up and women loving them. […] On one hand these lyrics are absurd. […] Yet on the other hand the songs are lovely. Their lyrics are unrelatable but the songs themselves are lovely. So there is the paradox of the human condition. And the media conditions us. We’re conditioned by a certain socio-cultural phenomena, in this case popular music, yet we can understand the conditioning and the value of the conditioning in the lyrics." 4

The artist plays with, plays back and subverts models (male, female and other), mapping out a mosaic of behaviours. Her research into the subject of identity, the self, the “I”, her observations, her worries, and her intuitions prefigured the discourses around identity that would eventually explode in the late 1990s, and that continue to inform us:

"Nobody ever was or had a self. All that ever existed were conscious self-models that could not be recognised as models. […] [Y]ou constantly confuse yourself with the content of the self-model currently activated […] Consciousness, the phenomenal self, and the first-person perspective are fascinating representational phenomena that have a long evolutionary history, a history which eventually led to the formation of complex societies and a cultural embedding of conscious experience itself." 5

Thus it is impossible to not recognize, in marshalore, different degrees of presence: physical, political, identity-bound, psychical. It is impossible to dissociate this presence from the material idea: figure, character, “onlooker,” a tool anchoring improvisation. The artist has explained what interests her above all: “To use oneself more precisely as a research instrument, as an experimental tool.” 6

Sometimes, the body, which is such a tool, allows for a reckoning, for measurement of the space framed by the camera, as in Ruelle en perspective (1977). In a Vancouver alleyway, marshalore approaches and retreats from the camera, traversing the framed space from left to right, from foreground to background, as far as a vanishing point where her presence becomes imperceptible, then returning to the camera, in so doing marking the boundaries of the frame and the depth of the shot. The artist reveals, with lucidity and stunning simplicity, that she is at once in and outside the recorded space, that any subject is mobile, unfixed, and that points of view are multiple. What at first glance appears to be an exercise—observation and exploration of a linear perspective—can, post-reflection, be interpreted as a metaphor for identity (fluid, inaccessible, about to disappear, absent and present).

body

Every time, with marshalore, the body is inhabited, to say the least: let us call this the essence of the creative process. This body, animate and suffused with affects, recalls the invaluable definition developed by Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari:

"A body is not defined by the form that determines it nor as a determinate substance or subject nor by the organs it possesses or the functions it fulfills. On the plane of consistency, a body is defined only by a longitude and a latitude: in other words the sum total of the material elements belonging to it under given relations of movement and rest, speed and slowness (longitude); the sum total of the intensive affects it is capable of at a given power or degree of potential (latitude)." 7

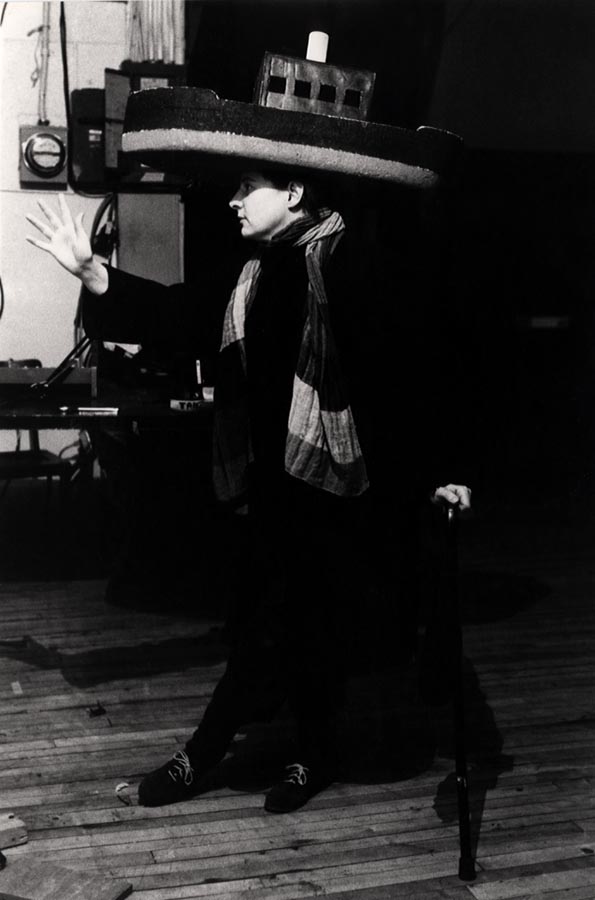

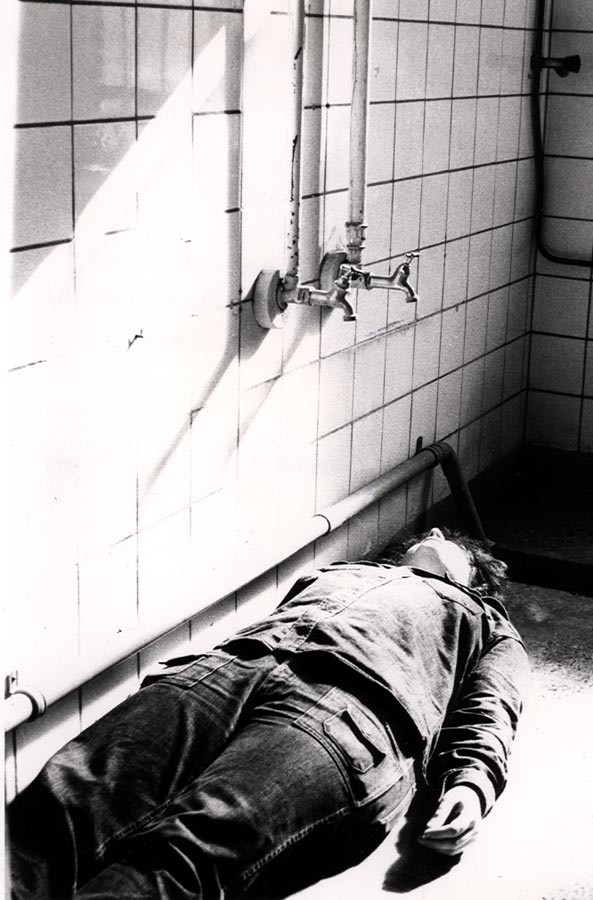

Any attentive observer of marshalore’s work will soon detect these relations of movement and rest, these affects to which Deleuze and Guattari refer. Unsettling and singular, they have shaken and continued to upset more than one spectator. The artist’s message is clear, direct, raw, unadorned. She asks us to look and to think: the invitation is at once critical, ironic and campy. Her photographs, videos, installations, and performances reveal a tension, perceptible in the way in which time slows down, stops, to leave room for the present of each action, be it narrated, commented or lived, or else executed before our eyes. In each work, a body bears the narrative and inscribes it in a given space—crystallizes the thought, the critical and political gaze behind the action. In that regard, two photographs—documents of an action conducted in 1979 by marshalore over three days in an abandoned prison in Amsterdam with a camera, a tripod and a timer—are worthy of attention here, as they harbour a number of elements that are emblematic of her body of work.

Drie Dagen, Drie Jaaren 1 [three days, three years 1] Photo © marshalore

Drie Dagen, Drie Jaaren 2 [three days, three years 2] Photo © marshalore

Notions of perspective, composition, light, and shadow are contained in them. Drie Dagen, Drie Jaaren presents us with a decidedly odd duet between body and space. The body anchors the action and its representation; gives it weight and presence. The body is a spatial marker for the viewer, much like a benchmark. This body, though, has a particular property: silent, listening for the space and its resonances, it is also immobile, recumbent. Experiencing duration, it catalyzes the silence and keeps us at a distance.

We find that same tension of scale (between body and space) in Trop(e)isme. However, in this video, which the artist describes as “a non-verbal sequence of distinct actions that seem to be interactions,” the body bursts from the screen, and the face, tragically, literally swallows the space and everything in it. Trop(e)isme is certainly the most animal-like of marshalore’s works, and one of the rawest.

Speaking of the raw quality of certain videos, Un Ode per un concettualismo italiano, 1977 is another work worthy of consideration, though more conceptual than Trop(e)isme. Marshalore described it as “a raw, but fully finished piece. The roughness of the porta-pak is an integral part of the production.” 8 That technological roughness envelops and extends the artist’s message.

duality

Very often, the artist’s body is located at the centre or peripherally: it then gains the status of a paradoxical observer. That oscillatory movement is expressed via different dualities: between behavioural study and improvisation; between game and confession; between agent and subject of an action:

"I think behavior has always interested me. Role-playing is a tool of therapists, behavioral psychologists. There are those who call themselves behavioral artists and they would say that rather than acting like behavioral psychologists, they start where behavioral psychology normally would end. They go past the peripheries of what psychologists would call behavior. I don’t know if I’m one of them but human behavior, the human condition, human nature interest me. So does the idea of acting the role interest me as well. So one way I would manifest a series of behaviors would be to put myself in the position of how such and such a person would act under such and such a condition and then I would play it out. And I really like the idea of improvisation as well. That runs through everything I do." 9

In the history of video and performance art, marshalore is such a presence. The artist has created a language all her own, a language that inhabits the body—a mad/out-of-focus body, her body, and those of the observers and spectators of her works. Often non-verbal, this language, consisting of movements, forms, sounds, and affects, extends a line of communication toward the Other. That call is perceived as a privilege: getting closer to the world of the artist, “Just the two of us.”10

See also: The Best of marshalore (video program)

Notes:

1. marshalore, brochure for a video program curated by Kate Craig (Western Front), 49th Parallel, New York City, November 26-December 22, 1983.

2. marshalore, Art et féminisme, Montréal: Musée d’art contemporain, 1982, p. 122.

3. marshalore, from a telephone conversation with Elizabeth Chitty, November 9, 2003, quoted in Elizabeth Chitty, “marshalore: Performing sound and image,” in Caught in the Act: An Anthology of Performance Art by Canadian Women, ed. Tanya Mars and Johanna Householder, Toronto: YYZ Books, 2006, p. 336.

4. marshalore, interviewed by Chantal Pontbriand, Three in Performance: Silvy Panet-Raymond and Michel Lemieux, marshalore, Elizabeth Chitty, Saskatoon: Mendel Art Gallery, 1983, p. 19.

5. Thomas Metzinger (2013), quoted in Sonic Thinking – A Media Philosophical Approach, ed. Bernd Herzogenrath, New York and London: Bloomsbury, 2017, pp. 201–02.

6. marshalore, from Elizabeth Chitty, “marshalore – Performing sound and image,” Caught in the Act: An Anthology of Performance Art by Canadian Women, ed. Tanya Mars and Johanna Householder, Toronto, YYZ Books, 2006, p. 336.

7. Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus, trans. Brian Massumi, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1980, pp. 260–61.

8. marshalore, from an e-mail exchange between the artist and Denis Vaillancourt of Le Vidéographe, winter 2017.

9. marshalore, interviewed by Chantal Pontbriand, Three in Performance: Silvy Panet-Raymond and Michel Lemieux, marshalore, Elizabeth Chitty, Saskatoon: Mendel Art Gallery, 1983, p. 17, 19.

10. This expression, an allusion to the song written by Bill Withers and recorded in 1980, is repeated by marshalore in various interviews. The artist has a passion for music, and words in song—an interest that is manifest in, among other works, the video You must remember this. marshalore is influenced primarily by sound. She says that she addresses her video work as a musician. Sound thus plays an important role in what she does, even in the case of a video without a soundtrack. That said, I enjoy associating the expression “Just the Two of Us,” with its connotations of intimacy and familiarity, with the relationship of attraction (attractive force) between marshalore (the performer, the videographer, the photographer) and the camera (video or still), alone with the camera. The expression also evokes the conditions of closed-circuit shooting with which video technology provided artists in the early 1970s—generative of an incalculable number of video performances, confessions and stories recorded in a one-on-one relationship between artist and camera. Lastly, this phrase can also refer to the intended close relationship (fictional or fantasized) between the work (the artist) and the observer, as if the work were addressed only to us, personally—as part of a privileged, intimate, exclusive relationship.

Translation: Michael Gilson